When we talk about Philippine independence, most of us remember two dates: June 12, 1898 and July 4, 1946. But the story of how the Philippines became a nation is not a straight line. It is a long, unfinished struggle marked by revolution, betrayal, resilience—and a fight to define who we are.

Before the Flag Was Raised

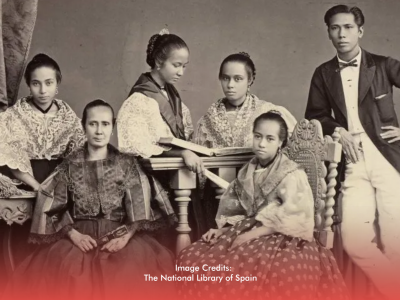

The Spanish ruled the Philippines for more than 300 years. They brought Catholicism, built churches and schools, and named our towns. But they also silenced dissent, killed reformists, and ran the country like a colony meant only to serve their crown.

By the late 1800s, ideas of freedom were growing. The educated class, led by figures like José Rizal, began to push for reform through writing. But it was the secret society of the Katipunan, led by Andrés Bonifacio, that turned thought into revolution.

In 1896, Filipinos picked up arms. The revolution spread. There were victories and betrayals. Bonifacio was executed by fellow revolutionaries. Emilio Aguinaldo rose to power.

Independence... Sort Of

On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo stood on the balcony of his house in Kawit, Cavite and declared independence. The Philippine flag was raised. The national anthem played. A country was born—or so it seemed.

The problem? No one outside the country recognized it. And at that very moment, the Spanish–American War was unfolding. The U.S. defeated Spain and took control of Manila. In the Treaty of Paris, Spain handed over the Philippines to the Americans for $20 million. The Filipino republic wasn’t even invited to the table.

The Commonwealth Years

When the Americans took over, Filipino forces resisted. What began as an uneasy alliance during the Spanish–American War turned into open conflict. In 1899, the Philippine–American War erupted.

It was brutal. Towns were burned. Civilians were caught in the crossfire. An estimated 200,000 Filipinos died from war, disease, and famine. Aguinaldo was eventually captured in 1901. The short-lived First Philippine Republic collapsed.

The U.S. declared victory—but it was a victory over a people who had already declared themselves free.

After the war, the United States established a civil government and promised eventual independence. The Tydings–McDuffie Act in 1934 set a ten-year timeline. In 1935, the Commonwealth of the Philippines was born, led by President Manuel L. Quezon.

It was a transition—autonomous, but not sovereign. Filipinos could govern, but the U.S. still controlled foreign policy and the military.

Then World War II happened.

A Country at War Again

In 1941, Japan invaded. The Philippines fell quickly. For three years, Filipinos endured occupation: forced labor, executions, famine. Resistance movements grew across the islands. The war left the country devastated—physically and emotionally.

When Allied forces returned in 1945, Manila became one of the most destroyed cities of the war. But it also marked the final chapter of colonial rule.

On July 4, 1946, the United States officially recognized Philippine independence through the Treaty of Manila. A ceremony was held at Luneta. The American flag was lowered. The Philippine flag was raised.

This time, the world recognized the Republic of the Philippines as a sovereign nation.

Reclaiming June 12

For years, July 4 was observed as Independence Day. But in 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal shifted the celebration to June 12—honoring the original declaration made by Filipinos, not the later one granted by a foreign power.

Today, we recognize both dates. June 12 stands for the act of claiming independence. July 4 marks its recognition. Together, they frame a larger truth: freedom isn’t something handed to us. It’s something fought for—again and again.